Diana Scott, University of Durham, is a Teaching Fellow in English for Academic Purposes (EAP) – supporting students with English language and academic skills as a foundation for their further study. Here she discusses the important role EAP support can play for prison learners, and how this links with her work on the Inside Out partnership between University of Durham and HMP Frankland.

I’m a trained Inside Out prison exchange programme facilitator and have worked with many cohorts of IO students, but I’m not an academic in a disciplinary department and I don’t deliver the main programme. For want of a better word I’m an ‘EAPer’ – an English for Academic Purposes (EAP) Teaching Fellow. At Durham, we’re based in the Centre for Academic Development, but we might be housed under yet another umbrella and name in your university.

We understand our remit as teaching students, any students, how to better engage with and perform well in their studies, with particular emphasis on written assignments. Academic skills; the ‘why’ of various academic practices, plus a good dose of discourse analysis is roughly what we teach. The university sometimes thinks we’re here to improve international students’ grammar. This is one of our great frustrations.

“One of Inside Out’s stated aims is to rekindle people’s intellectual self-confidence, but without clear understanding of what is expected of their written output and how it can be improved, this aim is at risk. EAP can mitigate that risk.”

One of our strands of activity is working in departments helping students to see what is expected of them on a certain assignment type and why, by deconstructing and reconstructing with them extracts of past student work. Another strand is our one-to-one consultations service for students where we typically act as ‘readers’ of draft work and then help the student writer to see where their text breaks down or drifts off, why, and how it can be improved. As ratios of students to academic tutors increase, assignment types proliferate, student backgrounds diversify, and fees rise, we see our role as vital and only fair.

So when I discovered that each term a cohort of incarcerated men or women were joining in an accredited university module I knew that we had to bring these services inside. One of IO’s stated aims is to rekindle people’s intellectual self-confidence, but without clear understanding of what is expected of their written output and how it can be improved, this aim is at risk. EAP can mitigate that risk.

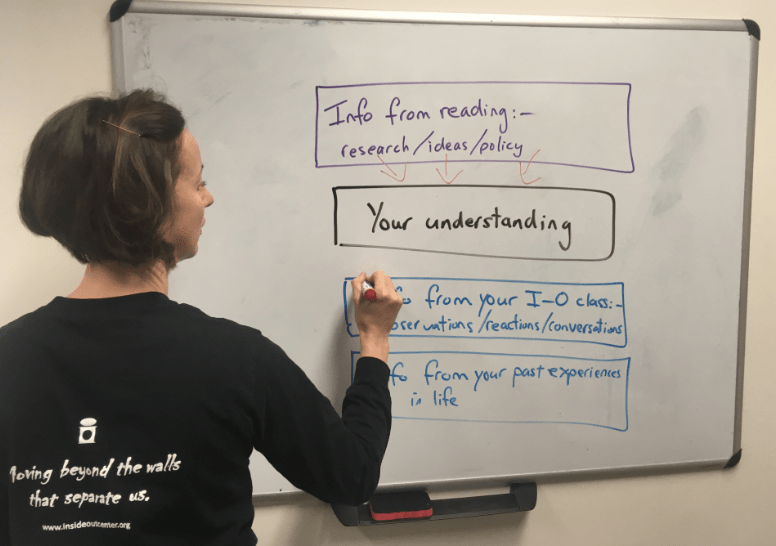

After pitching to our local IO think tank of insider alumni, reading through files of past student work, and talking to the IO tutors, my EAP colleagues and I re-designed and aligned the course’s reflective writing guidance and assessment criteria, ran reflective writing workshops inside and out, offered one-to-one consultations to outsiders, and went into prison a couple of times a term to offer consultations to insiders.

“Our position on the margins of a university is good preparation: your prison gym, chapel or library space doubling as a classroom is no more challenging than the college common room I was teaching in the other evening.”

During the writing workshops the insiders realised they had both strengths and weaknesses in their writing, just like the outsiders did. Whereas the insiders were more readily able to reflect on the personal, the outsiders were more readily able to reflect on the academic. Their assignment, however, required both. For the insiders, that moment of realising they weren’t at any disadvantage was incredibly empowering.

Now I haven’t mentioned the logistics of all this: readers of PUPiL will know that when it comes to collaborating across the walls, to say patience and flexibility are required is an understatement. There might be concerns about whether EAP colleagues will ‘get it’, but in many ways our position on the margins of a university is good preparation: your prison gym, chapel or library space doubling as a classroom is no more challenging than the college common room I was teaching in the other evening. Most EAPers were previously TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language) teachers abroad. This experience of working in an under-funded, chaotic language school on another continent can be helpful in adapting to some of the resource limitations and unfamiliar rules of the secure estate.

In addition, dialogic community-based teaching is no surprise to former communicative language teachers also trained to design activities that foster meaningful group discussion and experiential learning with multiple techniques for ensuring every member participates. We have more in common than you may realise. We’re in your university somewhere. And I think we can help.

Want to set up your own partnership or get tips for an existing collaboration? Our PUPiL toolkit shares the what, how and why of prison-university partnerships.

This is part of the Prison University partnerships blog series, which shines a spotlight each month on an example of prisons and universities working in partnership to deliver education. If you would like to respond to the points and issues raised in this blog, or to contribute to the blog yourself, please contact Helena.