Conference organisers Phil Heron and Rosie Reynolds

Space, coding and the science of sleep were all part of the equation at the PUPiL network’s latest event, as we heard from experimental projects that push the boundaries of what is usually possible in prisons.

The event was organised by PET’s Rosie Reynolds and Dr Phil Heron at Durham University, whose Think Like a Scientist programme introduces people in prison to concepts including climate change, plate tectonics and black holes.

From Prisoner to Scientist

Dalton, a former resident at HMP Low Newton, received a standing ovation for his talk about taking part in the  programme.

programme.

“Prison is seen as the last stop,” he said. “It’s the place society says: ‘keep them, we don’t want them’. Education, said Dalton, felt like a “pocket of air in the mess and noise”; a respite in the “eat, sleep repeat of prison life”.

The Think Like a Scientist course, “taught me stuff I only dreamed about,” he said. “I was asking questions, but rather than being told I’m stupid I was told that’s what scientists do – ask questions, complete theories, make arguments, think critically and analyse.”

“When we went onto climate change I realised I had fixed views from half-listened-to and outdated experiences. I read each article again and again – even when we talked about plate tectonics I went back to my wing telling people what I had learned.

“I was charting the impact of mood on sleep, writing my presentation on Alan Turing for the £50 note. I was learning, exploring, researching, forming an opinion. I was part of the solar system, the universe – not just me in a block, in a wing, in a room alone.”

Scotland’s Science Success

Over the border, the Cell Block Science programme has found huge success bringing informal science education to Scottish prisons.

Over the border, the Cell Block Science programme has found huge success bringing informal science education to Scottish prisons.

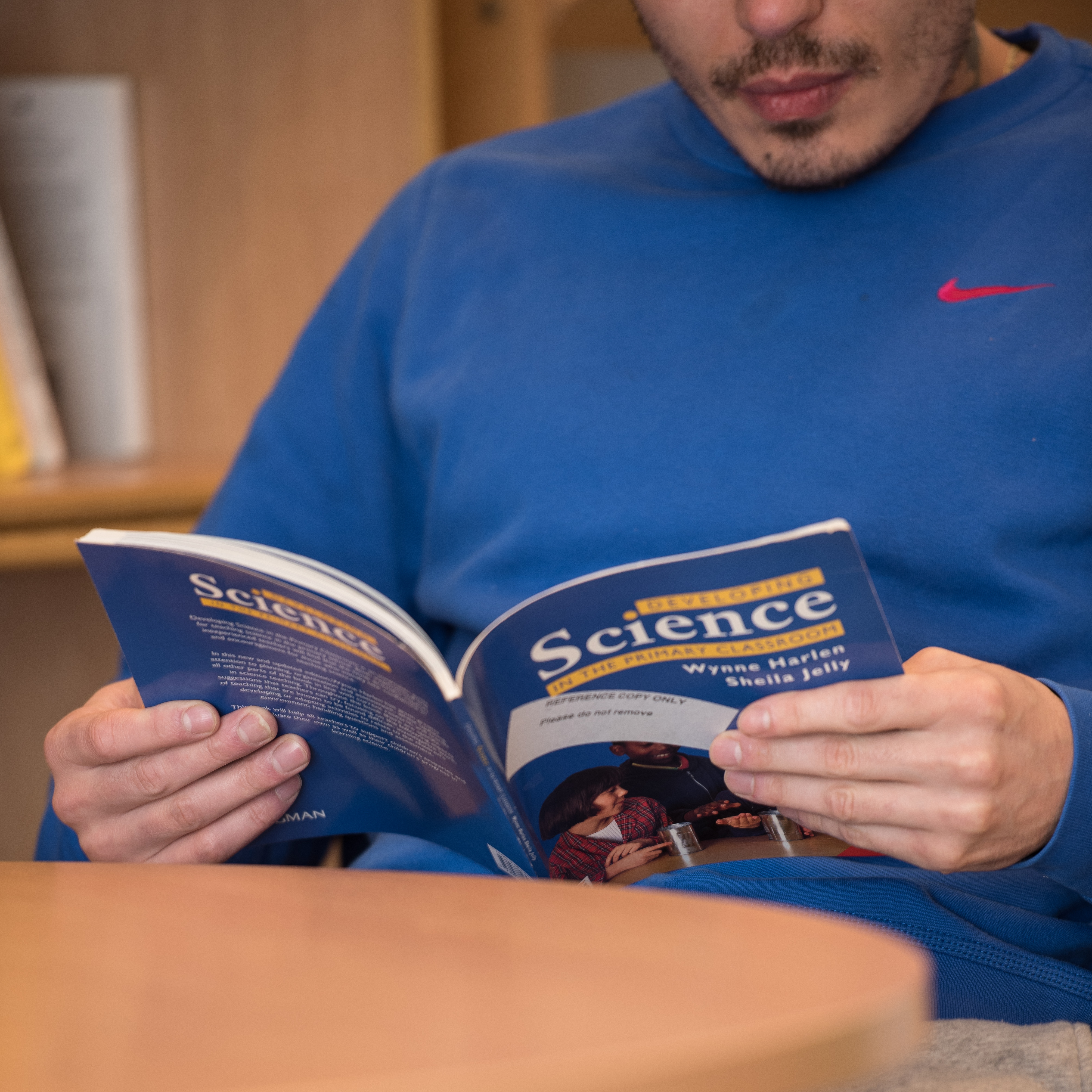

The programme is led by University of St Andrews in collaboration with numerous academic and non-academic partners. It works by setting up ‘science learning centres’ inside prisons, bringing academic researchers in to lead hands-on projects. The project also involves family learning sessions, holding science fairs during visits.

The project has been run in six Scottish and one English prison. Getting it to this point has required a gradual build up of trust with the prisons involved, said Project Lead Dr Mhairi Stewart, as “prisons perceive science as a general risk”. Thanks to her team’s efforts, they have gained approval to carry out heart and lung dissections inside, and bring in meteors.

Cell Block Science was co-produced with participants, with the name and logo chosen and designed by them. “We asked what do you like, when would you like it, how should it be delivered, what benefits could there be for you,” said Mhairi.

At first it was difficult to get researchers involved, but the project now has waiting lists of a year. Mhairi emphasised that when selecting these faciliators, “It’s important to remember that going into prison is not a novelty; it’s a privilege.”

Mhairi said the project was beneficial for all involved. Learners reported an increase in their knowledge and skills; researchers gained in terms of personal and career development; and institutions benefited through outcomes linked to outreach and research. “It’s important to share the benefits that residents are bringing to the university by taking part,” she said.

Cracking the Code

Code 4000 is the only prison coding scheme in the UK, currently operating in 16 prisons. Programmes Director Jim Taylor said the project aims to solve two problems at once: first, prisoners’ lack of skills that help create a “stubbonly high reoffending rate”, and second an employment market that is “crying out for digital skills”.

Taylor said the project aims to solve two problems at once: first, prisoners’ lack of skills that help create a “stubbonly high reoffending rate”, and second an employment market that is “crying out for digital skills”.

“In today’s workplace, digital skills are no longer an option,” said Jim, with 82% of jobs advertised online requiring digital skills, and those that do paying higher wages.

Prisons are currently woefully positioned to meet this need, he said, using “outdated equipment in pursuit of qualifications that will no longer be valuable”.

Code 4000’s programme trains people in the basics of coding, before moving them onto real-world projects with external clients. It has been received extremely well by the students, said Jim.

“The hunger to learn to code is absolutely fantastic to witness, I’m blown away by how much they take to it,” he said. “In one prison they are currently lobbying for the workshop to be open over lunch.”

The organisation aims to help people find full-time jobs in the tech industry after release. A recent graduate has just started work as a Java developer for a bank – earning what Jim believes is the highest starting salary for an ex-prisoner helped into employment.

Art, Expression and Writing Jailbirds

In the event’s keynote, Mim Skinner drew on her work as an art teacher in a women’s prison, an experience which inspired her book Jailbirds.

In the event’s keynote, Mim Skinner drew on her work as an art teacher in a women’s prison, an experience which inspired her book Jailbirds.

Mim was driven to share some of the shocking realities she saw as part of her work; the fact that 53% of women end up in prison for committing a crime to support the drug habit of someone else, and a third of the women were being sent home to no address.

Mim worked in a women’s prison, running arts and drama classes.

“Many of the women did not feel able to communicate in the right terms or share what they mean”, said Mim. “I had never realised what a privilege it was to be given words to say what I was feeling. What was missing in that group wasn’t intelligence, ideas or aptitude, it was just a set of tools to express themselves in words.”

Now working as a support worker in resettlement, Mim continues to employ women who have been in prison.

A resident’s artwork, inspired by a prison officer

“They are an amazing resource of lived experience and skills,” she said. “There is no one better at conflict management.”

The BBC has recently bought the rights to turn Jailbirds into a BBC series, which Mim is helping to produce.

A (Space) Portal Between Science and Art

Prisoners themselves were the writers at HMP Leicester, where residents were invited to stretch their minds infinitely beyond prison walls in a science-arts project called Space is the Place, run by writer Dorigan Hammond.

Prisoners themselves were the writers at HMP Leicester, where residents were invited to stretch their minds infinitely beyond prison walls in a science-arts project called Space is the Place, run by writer Dorigan Hammond.

The project invited residents to respond imaginatively to the idea of space, through spoken word, flash fiction and art.

“We wanted to open up a portal between science and art, and find out what would happen,” said Dorigan. “We were asking them to imagine a place unconfined by the prison walls. It’s a stretch asking people who can’t look up into the night sky to even think about it.”

Dorigan said she chose space as a topic “because it was big and sexy”. “It’s a really easy route to get people excited who think science is not for them.”

The project’s principal was to be inclusive, she added. “It needed to be something that everyone could take something out of and produce something at the end, whether it was drawing a picture, writing a poem or anything else,” said Dorigan. “We gave participants agency – to choose what to learn, to create, to explore the subject.”

“We don’t use the ‘e’ word, there’s a feeling of ‘education – no way’,” she said. People who took part, she said, tended to be “education avoiders”.

Dorigan collaborated with National Prison Radio to produce a programme about the project. It was presented by participants, one of whom reflected: “Just because we’re considered the lowest in society doesn’t mean we don’t have art in us.”

The conference also heard from:

- Francesca Findlater at Bounce Back about their projects linking science qualifications to jobs in construction.

- Karen New spoke about the Open University Journal Club’s introduction to prisons.

- Louise Dowell, Senior Librarian and HMP Leicester, shared her experience of facilitating science projects inside.

- Durham University’s Vice Chancellor Professor Stuart Corbridge kindly introduced the conference, drawing on his own links to prison education, including a spell teaching sociology at HMP Whitemoor.

Want to set up your own partnership or get tips for an existing collaboration? Our PUPiL toolkit shares the what, how and why of prison-university partnerships.

This is part of the Prison University partnerships blog series, which shines a spotlight each month on an example of prisons and universities working in partnership to deliver education. If you would like to respond to the points and issues raised in this blog, or to contribute to the blog yourself, please contact Helena.