The John Howard Centre is a medium-secure forensic hospital for adults. It treats people with a range of mental-health conditions and cognitive profiles, including global learning disabilities, detained under the Mental Health Act following contact with the criminal justice system.

Patients come to us either from prison or as a result of a hospital court order, while some may be admitted from general psychiatric settings. From a medium-secure hospital patients may be discharged into the community, or transferred to low-secure services and other step-down units. Some may be transferred to high-secure services, whilst others will return to prison.

Education in the secure estate

It is no secret that the history of education provision in the so-called ‘secure estate’ is a fraught and marginalised one, linked to the troubles of the FE landscape more generally. We are a group of practitioners working in highly complex environments who remain in need of formal recognition of our teaching expertise.

The conventional model of initial teacher training ‘does not go far enough’ in the context of those working with young offenders. The conclusion was that training ‘should include a specialism in offender learning’.

As long ago as 2013, the Institute for Learning’s Transforming Education In Youth Custody paper, advocating for reform on behalf of teachers in the sector, reported that the conventional model of initial teacher training ‘does not go far enough’ in the context of those working with young offenders. The conclusion was that training ‘should include a specialism in offender learning’.

As a team of qualified teachers who came to work in a forensic hospital setting through a variety of routes, our own position in relation to the more mainstream reaches of the sector (prisons; YOIs) is difficult to place. Even a 2016 Guardian article, Better than prison: life inside the UK’s secure hospitals, touched on the repercussions for patients around issues of education, without referring to the work of an education department or similar. If other hospitals are anything to go by, it’s probable that there was such a department or at least some in-house provision available.

Engagement

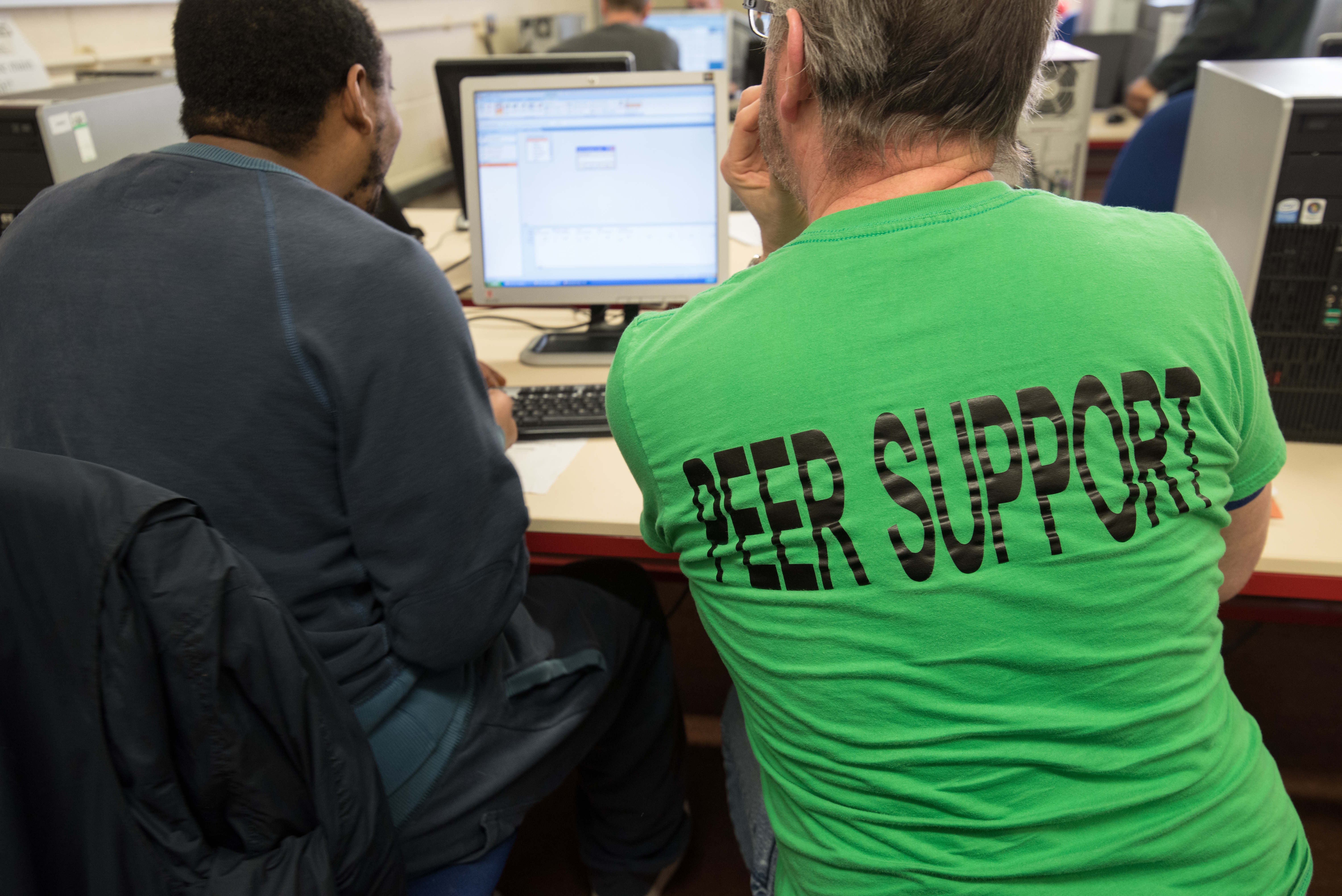

At the John Howard Centre we offer small-group and 1:1 tuition in Literacy, Numeracy, ESOL and ICT from pre-Entry Level to Level 2. We are an exams centre accredited to OCR and English Speaking Board, and so patients have the opportunity to achieve a range of qualifications with us, including in Functional Skills.

We support patients to access a variety of alternative courses

We support patients to access a variety of alternative courses through the futurelearn.com platform, and to study at degree level with the Open University, or to attend colleges in the community. As a department we work with the Forensic Recovery College across our NHS Trust’s medium and low-secure services. Our work includes dedicated provision for the Learning Disability service, as well as assessment for specific learning disabilities and cognitive abilities more broadly.

Unlike teachers in much of the secure sector, we don’t have to manage the cyclical re-tendering of education contracts. As an NHS-funded education department, we have the substantial luxury of goals around engagement, rather than around enrolment, retention and exam outcomes.

This means that while research into prison educators’ perceptions of their work (UCU/Institute of Education, 2014) has previously reported ‘strong concerns about not being able to provide sufficient support for the most vulnerable learners and those with a need for the most educational support’, we have the time and space to think about support on an individual level, and the challenges involved.

Teacher Zoe Gerrard described those suffering from mental health conditions/disorders who have offended as ‘amongst the most socially excluded groups in the country, the stigma of mental illness compounded by several years of enforced hospitalisation and prejudice fuelled by the media’

Writing in Reflect magazine in 2010, teacher Zoe Gerrard described those suffering from mental health conditions/disorders who have offended as ‘amongst the most socially excluded groups in the country, the stigma of mental illness compounded by several years of enforced hospitalisation and prejudice fuelled by the media’. To work as a teacher in this context requires an approach that has much in common with all teaching practice, inflected by the dynamics of the hospital environment.

Understanding our learners and their backgrounds

When we begin the screening and then initial and diagnostic assessment processes with a patient, it may be in the context of an incomplete picture of a person’s education history, often with little handover around education from previous institutions. This will often be the patient’s first experience of education in years. As David Holloway writes in his chapter, Mental Health and the emotional aspects of learning mathematics, ‘A numeracy lesson is not only a cognitive event, but also an emotional event’. Just as any learning is driven by the student’s experience of the world, it is our job to support a patient to tap into and negotiate her/his experiences of the world in as productive and independent a manner as possible.

This will often be the patient’s first experience of education in years.

In the context of a secure hospital and the complex histories and worlds of the people living there (as with any adult learner’s history), this needs to be approached in a way that acknowledges such histories and experiences sensitively. At the same time, this process of acknowledgement must avoid consciously or unconsciously constructing these experiences as deficits, or confusing the clinical boundaries of our relationship with the student.

Individualised support

Our work must respond on an individual basis to the specific experiences of education informing the student’s attendance in our sessions, and the many different motivations our students may have for attending. Where one student may have the confidence to attend sessions regularly and the desire for a more formal kind of work, provision for another student may constitute a brief session on a ward balcony or in a hospital café, in which the goal is principally that the student attends at all. Goal setting and schemes of work must as a result be similarly flexible, bearing in mind the impact that life in hospital can have on a student’s ability to attend.

Where one student may have the confidence to attend sessions regularly and the desire for a more formal kind of work, provision for another student may constitute a brief session on a ward balcony or in a hospital café, in which the goal is principally that the student attends at all.

An exams-based, outcomes-focused approach would therefore be entirely inappropriate – not to mention impossible. Exams and certificates can be of great practical use and validation to a student in hospital, just as they can be of use to us in anchoring the boundaries of a session. But they are a small piece of a multi-dimensional jigsaw.

This all adds up to our team’s contribution to the network of relationships intended to provide trust and consistency for the patient. Admissions in forensic healthcare can be lengthy, which means that you get to know the patients well.

Education as therapy

As a department, we work closely with clinicians such as occupational therapists, psychologists, speech and language therapists, social workers and nursing teams.

For some patients, education may be one of the few therapies they engage with. It can be a crucial source of meaning in their rehabilitation.

The information we can offer them is part of a process of painting the bigger picture of life for a given patient at a particular moment. We also have a role in promoting nuanced ideas around, for example, literacy and numeracy, in an environment where institutional preconceptions can be projected onto patients as powerfully as those projected by patients onto their own work.

For some patients, education may be one of the few therapies they engage with. It can be a crucial source of meaning in their rehabilitation. And to work in an environment such as ours is to witness the resilience of many of the people detained here.