In this blog, Angus Jackson talks about his experience as a university student participating in a prison-university partnership ‘Writing Together’, set up by Learning Together, and what learning as part of the group meant to him.

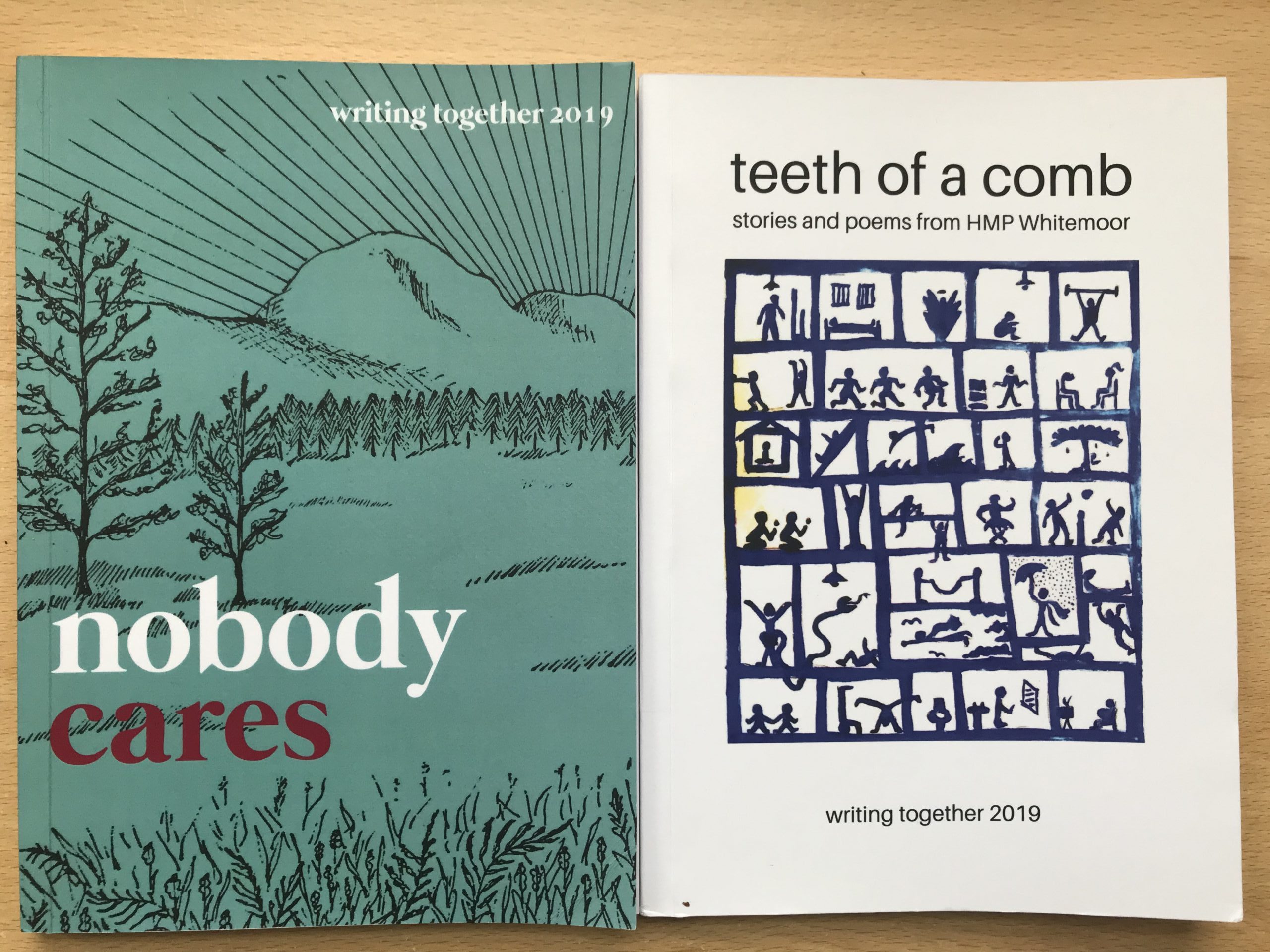

The course was held over six afternoon-long sessions in HMP Whitemoor over six months, and ended with the publication of two poetry anthologies and a celebration day in the prison with readings for family and friends and special guests.

A Big Idea

The Writing Together programme has its origins in an idea: put sixteen strangers from different backgrounds in a workshop, tell them they are writers and convince them they have a story worth telling. What emerges will be transformative.

Learning Together, a national network of partnerships between criminal justice and higher education organisations founded at the University of Cambridge, is grounded in criminological and pedagogical evidence about how learning communities can be built and nurtured in ways that disrupt – rather than entrench – prejudices by equipping and connecting people in ways that support positive growth.

We learn best when we learn together, whoever or wherever we are

By emphasising the role of intergroup contact, Learning Together works to overcome the power structures, exclusions, and hierarchies often encoded in ‘traditional’ learning environments – both in prisons and in ‘mainstream’ education. They propose we learn best when we learn together, whoever or wherever we are.

In this way, Writing Together also stems from knowledge; from the conviction that theory and evidence matter in how you conceive of and operate partnerships, especially in criminal justice settings where ‘theory’ and ‘evidence’ are so often twisted or manipulated for harshly punitive ends.

‘You are all writers’

Having taken part in the Writing Together course for two years, once as a participant and once as a mentor, I have experienced how this theory, and the evidence it draws on, feels in practice. I understand it, first-hand.

Sometimes I felt it in big and obvious ways: being told in no uncertain terms by our brilliant course coordinator and novelist Preti Taneja, on day one, that everyone in the room was a writer, even when we didn’t believe it ourselves. No prisoners, or Cambridge students. No ‘us’ and ‘them’. Just a ‘we’.

It brought us together, in that small, crowded room in the prison chapel, as writers

Or, a few weeks later, discovering this writerly identity for ourselves when every participant read a piece of work they had written in response to a poem by Ahmet Alan, a political prisoner incarcerated in Turkey called ‘A Voyage Around My Cell’. These readings revealed an extraordinarily broad canvas of experience and many different interpretations of the word ‘cell’. But it brought us together, in that small, crowded room in the prison chapel, as writers.

The meaning of ‘writer’ changed for me – it no longer became an identity of distinction, but a meeting point

I will always remember this moment. It was the moment when the meaning of ‘writer’ changed for me – it no longer became an identity of distinction, but a meeting point; a site where institutional divisions and what we are told about specific groups of people could be unlearnt and reformulated, a place where we could write back against stigma and inscribe our necessary interdependence as human beings.

I felt in practice what I had always believed in theory: that my future depends on your future and that difference is a source of strength rather than division. As one participant, Nathaniel, wrote in his ‘Voyage Around My Cell’ piece that day: ‘I took you on a voyage of my cell so you can understand me better. If you would like to write back, I am here.’

Collaboration to Creation

But these feelings were also experienced in smaller, subtler ways. For instance, during a word-association game when a seemingly spontaneous and tongue-in-cheek suggestion, ‘Nobody Cares’, was taken up by the group and eventually became the title of our anthology in my first year.

Or, in my second year, when exchanging lines of poetry with one resident in a Japanese form known as Renga to collaboratively produce ‘Justice Is…’, a piece in which each line carries forward something from the last:

The justice of the knife can leave you with a sentence for life

But your life means much more than the sentence

And the sentence carries the meaning you give it

And what you give it lives on

By any means necessary.

Reading back over this poem, written quickly and spurred on by the expectant gaze of another, I can no longer remember who wrote which lines. But authorship does not matter; it was written together.

There was laughter too, nervous at first as stories were shared over tea and biscuits, all mumble and anticipation. But soon that laughter became full-bellied. We no longer needed the tags bearing our names, given to us all on day one. The workshop bristled with hearty handshakes and warm chatter.

We partnered off, one Cambridge student to one Whitemoor resident, and exchanged drafts, edited each other’s work, and slowly, step-by-step, constructed an anthology

Then, sit down and pick up the pen and write. ‘Free writing’ first, without any restrictions whatsoever, spurred on by association, feeling our way. What do we want to say, and why? Personal stories, trust building. Then, prompted by Preti, how are you going to say it? What about a rhyme here? Try writing from the second person. Switch to the past tense here. Don’t chew your pen. Let’s try acting this bit out. Off into groups. Write, write, write…

Gradually, we moved from the purely personal into the imaginative and then slowly honed in on the crafted and formed.

We partnered off, one Cambridge student to one Whitemoor resident, and exchanged drafts, edited each other’s work, and slowly, step-by-step, constructed an anthology which was sent to the printers, and eventually published. No one could have any doubts now: we were all writers.

Floating Clouds

These finished objects, the printed anthologies ‘Nobody Cares’ and ‘teeth of a comb’, are two of my most treasured possessions. They are testament to an extraordinarily dynamic process that involves many institutions and courses run in prisons up and down the country.

But more than this, they are testament to the people that the programme brings together, and the stories they carry with them: academics and prison educators, published writers and professional practitioners, university students, prison residents and even staff, like one officer, Al, who joined our course on my second year and had his work included in the anthology.

Learning Together, and prison-university partnerships like it, demand that we ask difficult questions of ourselves and of each other

They are also the product of a deep and necessary discomfort. Learning Together, and prison-university partnerships like it, demand that we ask difficult questions of ourselves and of each other, as well as of the partnered institutions.

Through connecting with others and being exposed to broader social spaces, students can connect with themselves in radically new and unimaginable ways

This is education not as the closed-off realm of levels and abilities, streaming and examining, but as an expansive process of self-discovery and political reimagining; through connecting with others and being exposed to broader social spaces, students can connect with themselves in radically new and unimaginable ways. It is education as the embodied, day-to-day work of freedom.

On what turned out to be our final bus journey home from Whitemoor (always quiet and reflective times) I wrote the following words in my notebook. They speak, I think, to the transformative potential of prison-university partnership courses like Writing Together – the possibility of opening ourselves more honestly to one another, to the institutions we live and work within, and, ultimately, to the world:

As we leave, the tannoy-system on its never-ending loop is still ushering us in: Welcome to HMP Whitemoor. We ignore its instructions and step out into the biting-cold, now-dark air. We take the bus home largely in silence. We come and we go from this place like clouds. We can: floating away – questions in the sky.

As well as writing this blog, Angus also volunteered with Prisoners’ Education Trust over the summer, monitoring prison education and supporting our policy work. Thank you Angus for your hard work and your contribution to supporting prison education.

This is part of the Prison University partnerships blog series, which shines a spotlight each month on an example of prisons and universities working in partnership to deliver education.

If you would like to respond to the points and issues raised in this blog, or to contribute to the blog yourself, please contact Helena.