Education has always been a priority for me. I’ve always enjoyed learning and fortunately, for the most part, I’ve been taught by teachers with zeal, dedication and a passion for education. Their inspiration has been key to my academic journey.

Education has always been a priority for me. I’ve always enjoyed learning and fortunately, for the most part, I’ve been taught by teachers with zeal, dedication and a passion for education. Their inspiration has been key to my academic journey.

To me, education — regardless of the subject — has always felt like learning a language, with each subject being a unique dialect. Throughout my life it has provided structure and guidance: from primary school, secondary school, summer schools and college, to university, prison and then university again — yes, even in prison.

When life disrupts the plan

Transitioning through the different stages of education teaches you to plan your journey in steps and phases — like pursuing an undergraduate degree, then moving on to a master’s, and eventually a doctorate. That’s how I had mapped out my educational path.

But then life happened — unforeseen, inescapable and nearly insurmountable. In my case, life meant prison.

Prison was never part of the plan — not my plan. I had spent five years falling in love with psychology. My passion for the subject was born out of my curiosity to learn and understand human behaviour: how the unique environments and experiences we all have shape and impact our perceptions and subsequent realities. This passion led me to pursue an undergraduate degree in the subject in the hope of one day becoming a clinical psychologist, helping those who for whatever reason face difficulty with poor mental health.

But suddenly, I found myself serving a long sentence, where the educational provisions left much to be desired.

Before prison, I had benefitted from what I consider an incredible comprehensive state-funded education, overcoming various social and educational barriers to reach university. However, once imprisoned, my education came to a standstill.

The prison’s education department offered nothing academically beneficial to help me continue my journey. In fact, the provisions for those just starting their educational journey or whose paths had been cut short earlier in their lives were, in my opinion, abysmal.

I quickly realised that many people in prison would never get the chance to fall in love with learning, even though we all had the time to do so. Prison education needlessly resembled nothing like the standard state provision, even though, in my opinion, it easily could.

Distance learning: a library in the jungle

Many things stand still for a person in prison, but one thing that doesn’t is the mind. In fact, I would argue that in prison, the mind truly comes to life. It can either be your worst enemy or your greatest ally. Whether you want it to or not, it will absorb the environment around you — the only control you have is over what you use to feed or distract it.

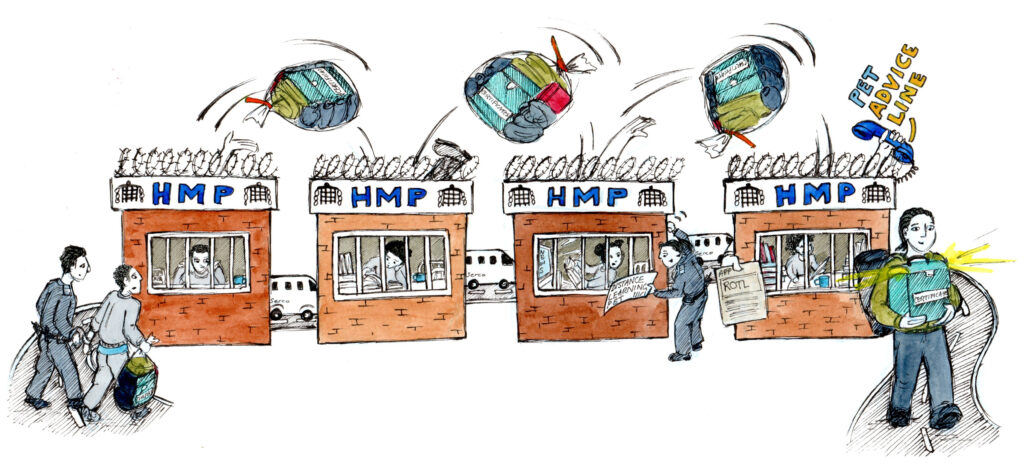

Until the prison’s Distance Learning Coordinator (DLC) approached me, I had been feeding my mind with books, the latest psychological research, politics and the chaotic news surrounding Brexit and the uncertainties of the world we lived in. Then, the DLC offered me something that my previous three prisons had not: the chance to continue learning.

In previous prisons, after completing educational assessments, I was deemed too advanced for their educational provisions and assigned to workshops (bagging breakfast packs or other prison duties). But this DLC introduced me to the idea of a self-taught distance learning course, funded by a charity I had never heard of — Prisoners’ Education Trust (PET).

In previous prisons, after completing educational assessments, I was deemed too advanced for their educational provisions and assigned to workshops (bagging breakfast packs or other prison duties). But this DLC introduced me to the idea of a self-taught distance learning course, funded by a charity I had never heard of — Prisoners’ Education Trust (PET).

With PET’s support, I enrolled in an A-level course in Law. Thanks to my previous studies, I had the tools I needed to engage with the material, and PET provided course funding, materials, tutor contact and a range of other support services too numerous to list. Most importantly, I had access to their Advice Line, which helped me navigate the natural barriers that come with studying in prison – of which there are many.

Studying through PET allowed me to keep my academic mind active and maintain my engagement in learning. Although I had completed A-levels before, completing just one in prison was an academic challenge I had never experienced the likes of before. The constant support was a necessity, especially as along the journey for multiple reasons I would become disengaged from and reengaged with my course.

I was able to successfully complete my A-level two years after I had begun and three prison transfers later – all while having been supported by PET.

A return to mainstream academia

Five years after I had to leave university, the opportunity for me to return arose once I was transferred to HMP Hollesley Bay, an open prison. Release on Temporary Licence (ROTL) allows people in prison the opportunity to be temporarily released daily to seek educational or employment opportunities and development.

For me the choice and desire to return to university required no hesitation, but would my university want me back after five years? The answer was yes!

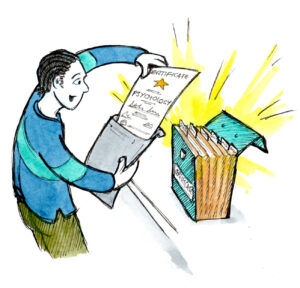

Being able to demonstrate that my mind had in fact remained academically stimulated during my time away, and that I was still the same individual, with the same promise, they had initially admitted (despite what life had thrown at me) aided their decision to readmit me. I returned to my course at the level where I had left, although had to restart the semester. My course, funded through PET, aided the opportunity to return to mainstream academia.

Studying while on ROTL involved challenges of its own. Readjusting to the implications of full time education while still being in prison carried a heavy toll; this was taxing mentally, emotionally and financially. The pursuit of my studies required a 150 mile round trip between prison and university every day, six days a week.

Eighteen months later, I had successfully completed my Bachelor of Science Degree with Honours in Psychology (First Class). I had also been released from prison.

The full circle moment

I would have been wrong to think my journey with PET would end in prison. Soon after my release, a vacancy opening afforded me the opportunity to continue my journey with and to work for PET as their Lived Experience Coordinator.

In this role — funded by The National Lottery Community Fund (TNLCF) — I coordinate the involvement of those with lived experience of the justice system in PET projects and workstreams. PET believes in placing lived experience at the heart of its service delivery. As part of this, we have several Lived Experience Consultants who use their experiences in prison to shape policy and actively consult on our projects, helping us to reach and support more people in prison.

My journey with PET began during a turbulent time in my life, but it has come full circle, continuing to impact me and others beyond my release.

Donate to PET and help people in prison find a new direction. You can also sign up to our email newsletter. Illustrations by PET Lived Experience Consultant Erika – find more of her work here.